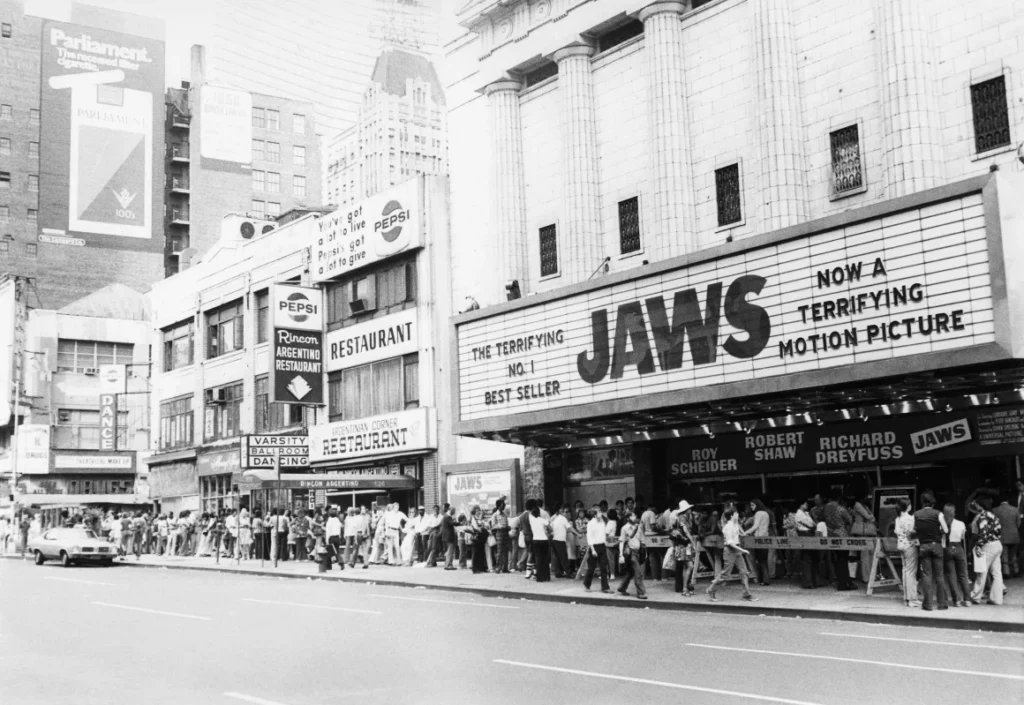

Universal/Kobal/Shutterstock

‘Jaws’ at 50: How a Movie Forged a Monster and a Mission

In the classic film “Jaws,” the cartilaginous villain remains largely unseen. It tears through its victims—a skinny-dipper, a dog, a small boy—with terrifying invisibility. Viewers wait nearly two hours to finally see the great white shark leap from the water and swallow the gruff Captain Quint whole. Until that climax, we mostly see its dorsal fin slicing through the waves before the water blooms into the color of ketchup.

Fifty years on, “Jaws” is still credited with inventing the summer blockbuster. It kickstarted a subgenre of shark-centric horror and inspired decades of suspense films. However, it also cemented a powerful and damaging myth. According to Jennifer Martin, an environmental historian at the University of California, Santa Barbara, the film inflamed our fear of sharks as malicious, man-eating monsters.

“I’m struggling to think of a parallel example of a film that so powerfully shaped our understanding of another creature,” she said. “They were killing machines. They were not really creatures. They weren’t playing an ecological role.”

Universal/Kobal/Shutterstock

The Reality Behind the Teeth

While the film preys on our fear of the unknown, it also stands in stark contrast to scientific reality. Real great white sharks are not as large as the demonic fish in “Jaws,” nor do they hunt humans for sport. They are certainly intimidating, and they do occasionally bite swimmers, sometimes with fatal results.

“Being bitten by a wild animal, and in particular one that lives in the ocean, was frightening for us already,” said Gregory Skomal, a marine biologist who has studied great whites for decades. “That’s really what I think ‘Jaws’ did — it put the fear in our face.”

Most shark researchers believe attacks are cases of mistaken identity. A shark may confuse a person on a surfboard for a seal, its natural prey. Skomal explains that they typically take a single bite, realize their mistake, and move on. This is a far cry from the film’s shark, which dispatches its victims with clear, vengeful purpose. As Martin noted, the film is so powerful because

“none of us want to look like food.”

Universal/Kobal/Shutterstock

From ‘Garbage Eaters’ to Man-Eaters

Decades before “Jaws,” great whites were not considered the ocean’s most fearsome predators. In the early 20th century, many were viewed as mere “garbage eaters,” feeding on waste dumped from coastal cities. They were pests, not monsters.

This perception shifted as humans began to invade their territory. With the popularization of scuba diving and surfing in the mid-20th century, people spent more time in the water, leading to more frequent encounters. “It was just a matter of time before people got nobbled,” said Gavin Naylor, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research. Local newspapers began picking up stories of run-ins, and documentaries like 1971’s “Blue Water, White Death” helped shape our view of sharks as creatures to be feared. But it was “Jaws” that cemented it.

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

A Legacy of Regret and Advocacy

The film’s influence was immediate and tangible. The glee with which Amity Island’s fishermen hunt sharks wasn’t entirely fictional. Shark fishing tournaments already existed, but “Jaws” brought new publicity to the sport of hunting “trophy sharks.”

“The killing of these animals became sanctioned, approved of, as a result of the film,” Martin said.

This “macho madness,” as he called it, was a source of great regret for Peter Benchley, who wrote the 1974 novel the film is based on. He lamented that his work of pure fiction caused audiences to view sharks as vengeful monsters. Benchley later spent many years of his life dedicated to shark advocacy and conservation, working to undo the myth he helped create.

Auscape/Universal Images Group Editorial/Getty Images

Why We’re Still Hooked on ‘Jaws’

While most audiences cheered when Chief Brody blew up the shark, many also left the theater fascinated. The morbid curiosity with a creature that could turn us into prey drove the success of “Jaws” and, eventually, decades of Discovery’s “Shark Week.”

“They are charismatic,” Martin explained. “They command our attention through their size… their morphology, their behavior.”

Ironically, the film that demonized sharks also enticed a new generation of marine biologists to better understand them. In the years since, the perception has slowly shifted from fear to fascination, respect, and a desire to conserve. We now better understand their vital role at the top of the underwater ecosystem. This appreciation is critical, as overfishing has caused several shark populations to decline.

Today, experts urge a balanced perspective. It’s wonderful to love and protect sharks, but we must also respect their power. “Sharks are becoming the new cuddly whales,” Naylor cautioned. “They’re not. They are predaceous fishes that are efficient.” For anyone who needs a reminder of the potential danger, the answer is simple: just watch “Jaws.”